Puffy eyes and double chins

German Renaissance

15th and 16th centuries

German Renaissance: And Cranach paints for the Reformation

The search for knowledge and truth leaves traces on canvases as well; in the studios of German painters like Albrecht Dürer, Lucas Cranach and Hans Baldung, new techniques for life-like portrayals of their motifs emerged. Realistic portraits, true-to-life proportions and a central perspective characterize the works of the German Renaissance.

Fast, faster, Cranach

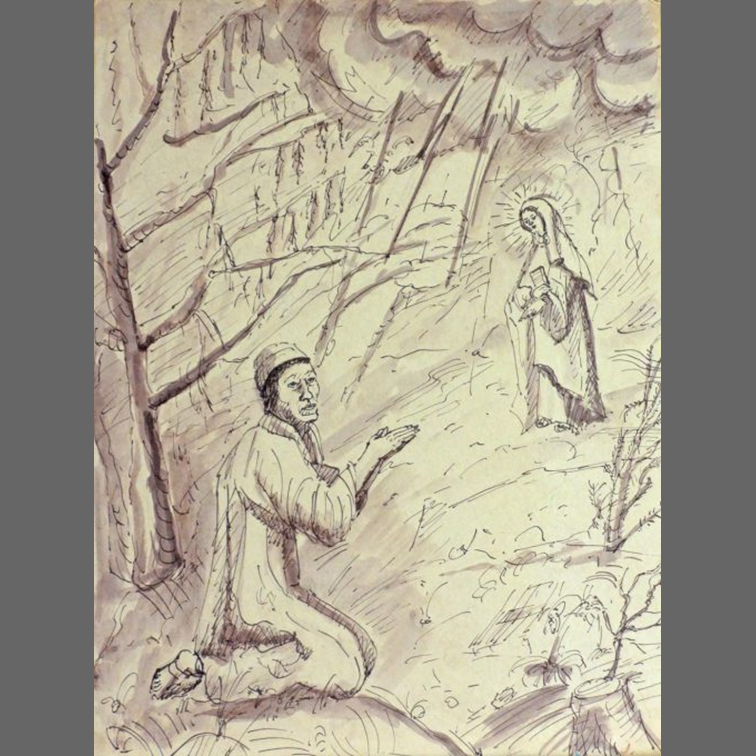

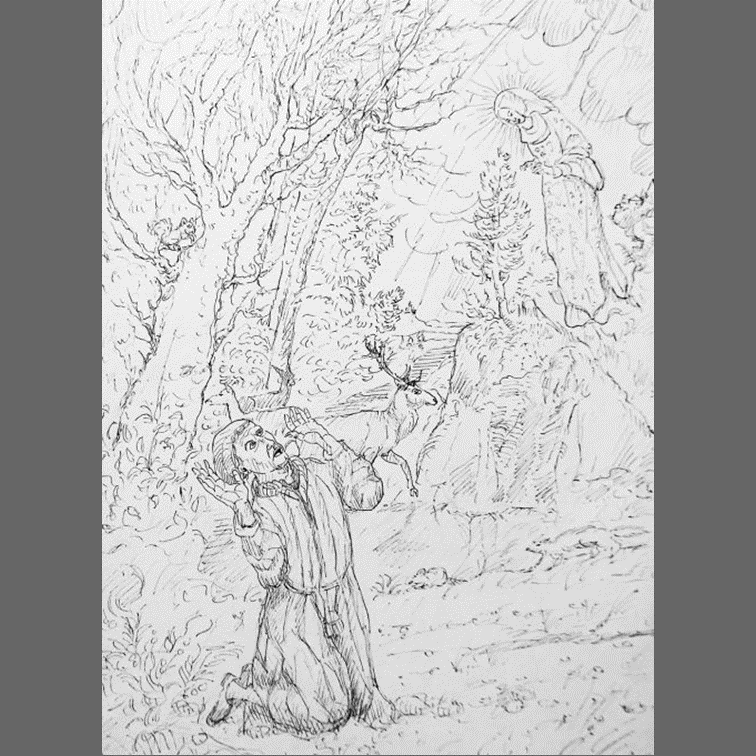

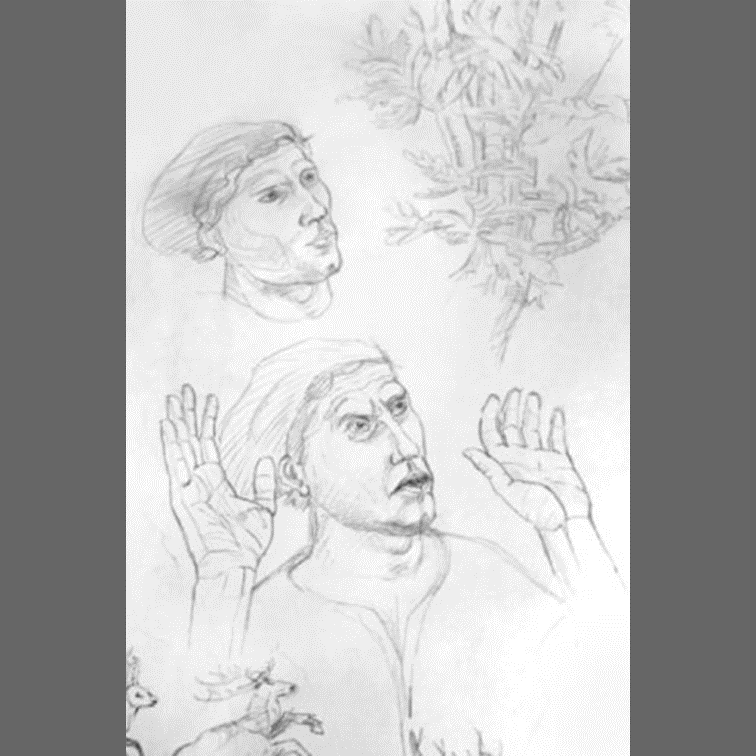

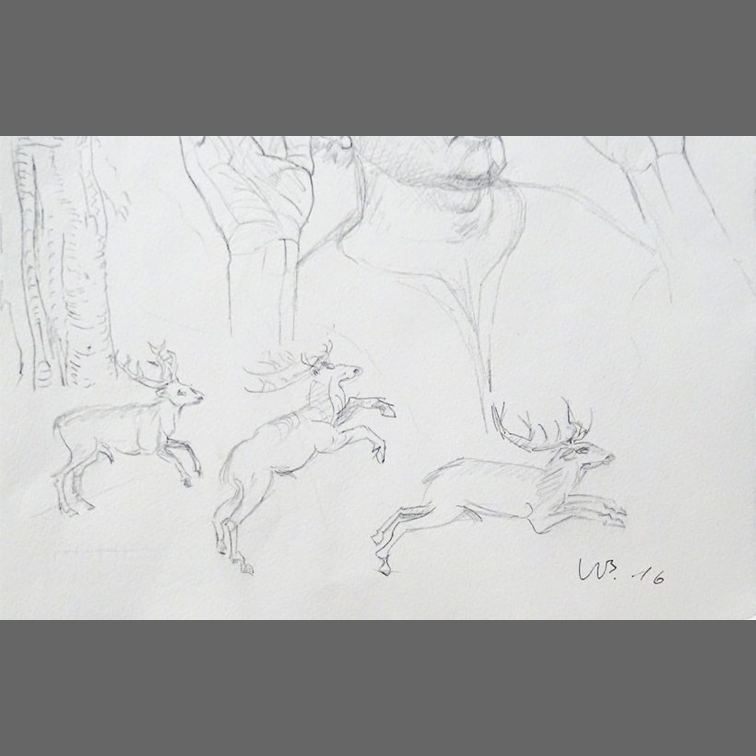

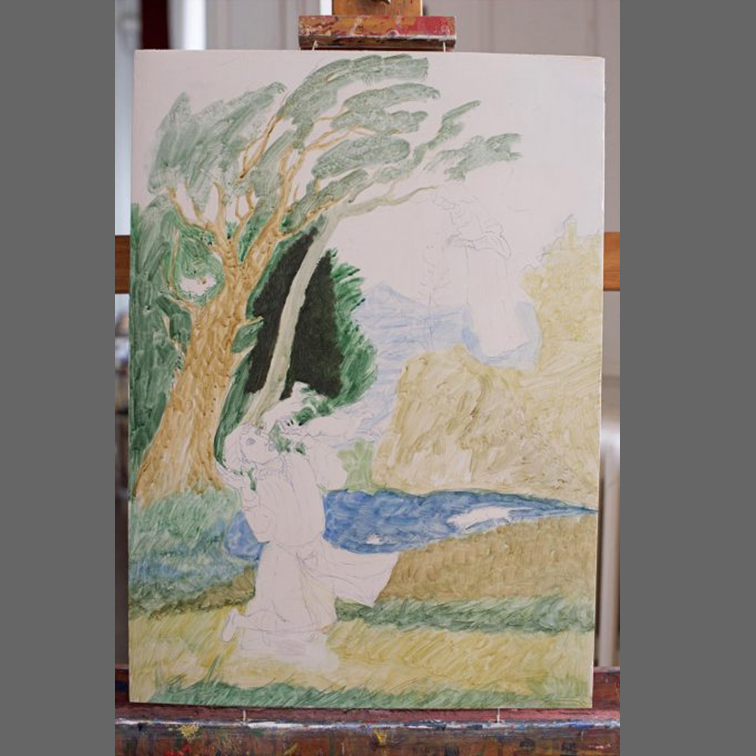

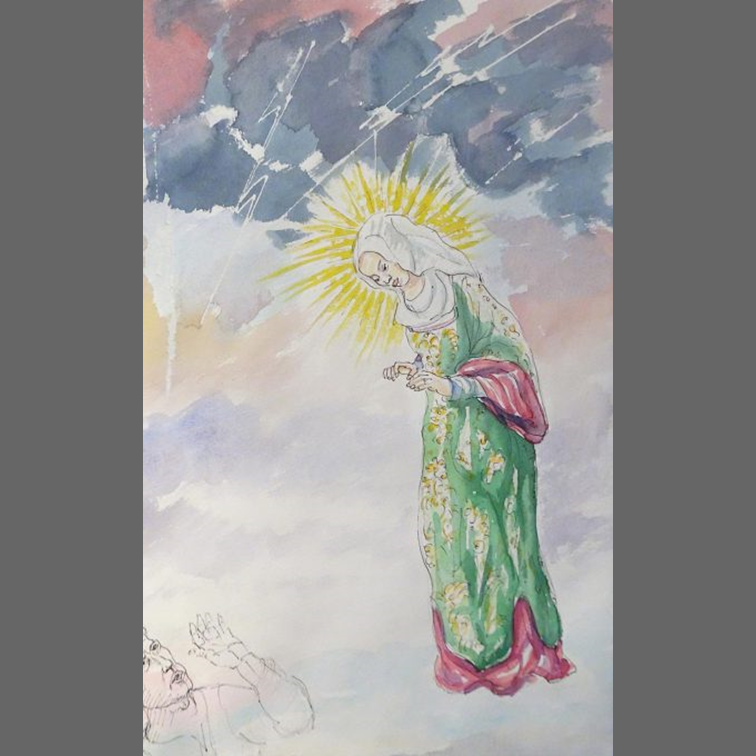

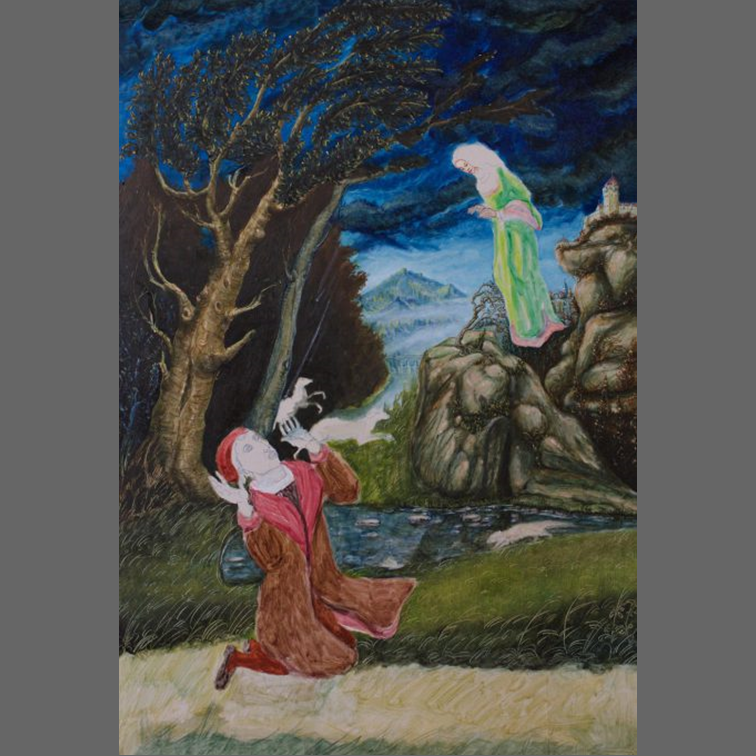

The Cranach studio was in effect a picture factory for the Reformation, but they never turned Martin Luther’s legendary thunderstorm experience into a picture. Wolfgang Beltracchi shows how it could have looked. The “speed painter” Cranach developed a highly efficient process. For fields and forests he used a dark prime coat and created form-shaping contours with a maximum of one to three colors. Flesh was primed with a very light color, painted over with skin tones and then modeled with lights and shadows. Use of various brushes, applied using dabs or strokes, helped him portray different types of surfaces. Cranach normally started from the center of the picture, working his way to the periphery, and his final step was to apply lights and shadows to faces. He usually completed his more elaborate-looking paintings in only a few weeks.

From idea to painting

“Help me, Saint Anne, and I will become a Monk.“ Wolfgang Beltracchi is painting the moment when Luther cried out, using the artistic voice of Cranach. Saint Anne appears often in Cranach’s work, so Beltracchi has clear references for her portrayal: among them the red coat symbolizing protection, and her headscarf, which resembles that of a nun. Cranach never painted Luther as a student, however. In this case, the artist is referencing other works from the era. The photo gallery shows how the work was created.

Martin Luther gets a red robe. Red as the color of fire, blood and love is figurative for enthusiasm, for “burning” for God. Carmine red is regarded as a sign of deep belief.

German Renaissance

Albrecht Dürer and Lucas Cranach the Elder are figureheads of the German Renaissance. Additionally, Hans Balding and the Danube School influenced German painting in the 15th and 16th centuries.

1. COURAGE TO SHOW THE TRUTH

True-to-life portrayal of people was central to German Renaissance painting. Nothing is glossed over: sagging breasts, idiotic expressions, sallow skin. What mattered most was adhering to reality.

2. CORRECT PROPORTIONS

In his relentless pursuit of the most realistic portrayal possible, Albrecht Dürer set new standards for the proportionality of forms. In his main written work about proportion theory “Four Books on Human Proportion” he presents his naturalistic, systematical studies of the human body. Published using the relatively new printing press method, they quickly spread throughout the European art scene.

3. FULL OF MEANING

The German Renaissance was still very rooted in symbolism, as was common in the Gothic period. A cloak stands for protection, cloves for the Passion of Christ, fruit for overcoming the original sin, squirrels and foxes, as companions of the Devil, for evil – the list of the symbols used goes on and on.

4. IN PERSPECTIVE

Use of the vanishing point for perspective was widespread during the German Renaissance. Introduced by Dutch and Italian painters, it was soon commonly used by artists throughout Germany.

5. PRODUCTIVE

Renaissance painters are quite productive. Dürer alone created around 90 paintings, 100 engravings, 300 woodcuts and 400 book illustrations. Lucas Cranach the Elder was unbeatable during his time; around 5,000 works were produced in his studio – with the help of apprentices, who used an easily acquired dabbing technique, thus leaving no traces of their own styles behind.

Eras of art in the KAIROS project

Medieval art

Early Netherlandish painting

Italian Renaissance

Mannerism

Early Baroque

Rokoko