CELEBRATING EVERYDAY LIFE

The Golden Age

17th century

The golden age: The new everyday life through the eyes of Vermeer

While the Baroque period was sweeping a wave of extravagance across the regions of Europe shaped by the church and feudalism, another, more down-to-earth style was emerging in the Netherlands. It was inspired by the everyday lives of a growing middle class, who had achieved prosperity in the young, tolerant, cosmopolitan republic with its flourishing trade. Their longing for images to be captured of their own successful lives led to an unprecedented demand for art, with hundreds of painters churning out genre paintings, portraits, still lives and other types of artwork in quick succession. Among the artists of this time was Anders Jan Vermeer. Only 37 paintings are known to have been produced by his hand, but most of them are absolute masterpieces. His secret lies in his subjects’ graceful stances and, even more importantly, in his special use of light. Vermeer’s painting technique was truly revolutionary. Even his contemporaries marveled at the interplay between light and shadow, his works full of tiny reflections making them reminiscent of photographs. To this very day, researchers have been left puzzled by his unusual technique and are still trying to work out whether he used any technical means to learn to see motifs in a new way. And if so, which tools he had at his fingertips.

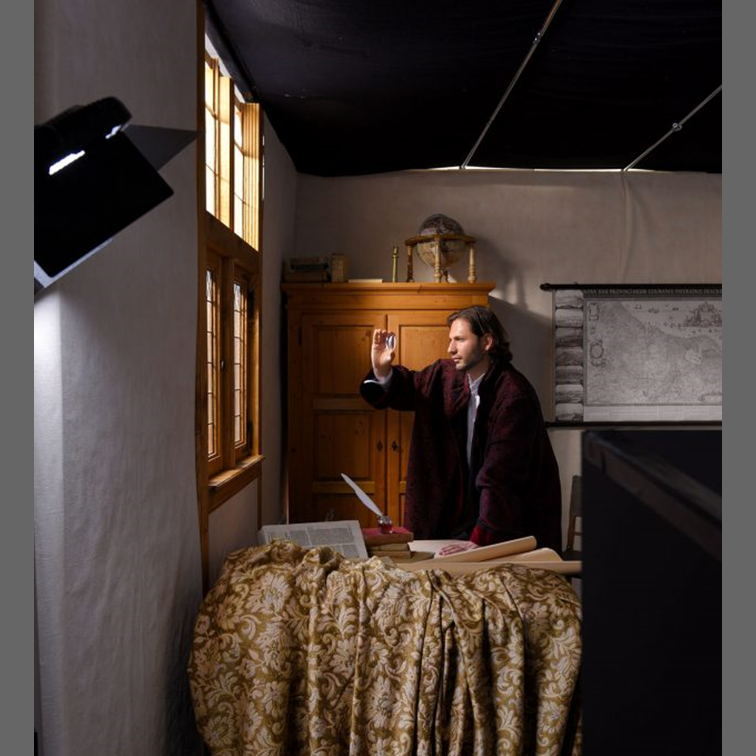

Wolfgang Beltracchi in ZOTT Artspace in Munich. After a month of planning, the recreation of Vermeer’s home studio is complete. Beltracchi experiments with adjusting the camera obscura – a technical tool that Vermeer may have had at his disposal.

MEASURING HEAVEN AND EARTH – AND THE HUMAN SPIRIT

The 17th century was marked by a paradigm shift. Science had previously been restricted by tight limits placed on it by the church. Anything that called into question the existence of a divine plan was scorned, if not completely repressed. However, seafarers and merchants were reliant on astronomy and cartography, meaning that new methods began to be used to investigate and measure the earth and space. Jan Vermeer recorded this progress in two famous paintings, considered by some to be a pair: The Astronomer, which he painted in 1668, and The Geographer, which he began working on in the same year.

At the same time, Baruch Spinoza was formulating his theoretical construct, according to which there is no dualism between God and the world, but rather the two form a single entity. This groundbreaking theory turned the philosopher into one of the greatest scholars of the 17th century.

Spinoza could even have served as inspiration for Jan Vermeer if he had gone on to create a third painting to go alongside The Astronomer and The Geographer – especially since the painter and philosopher both lived in the Dutch city of Delft and knew each other. Perhaps Vermeer even ordered the very lenses from him that he could have used to visualize the light effects against the shaded background that remain unique to this very day. The lasting impact that Spinoza’s anonymously published philosophical work was to have on the modern world only became clear much later. Drawing on the knowledge available to us more than 250 years after Spinoza’s time, Wolfgang Beltracchi painted the philosopher in a study like the one that had already served as the backdrop for The Astronomer and The Geographer.

The team at ZOTT Artspace recreated Vermeer’s study as depicted in The Astronomer and The Geographer. Test photos like these were used to examine the composition of the image.

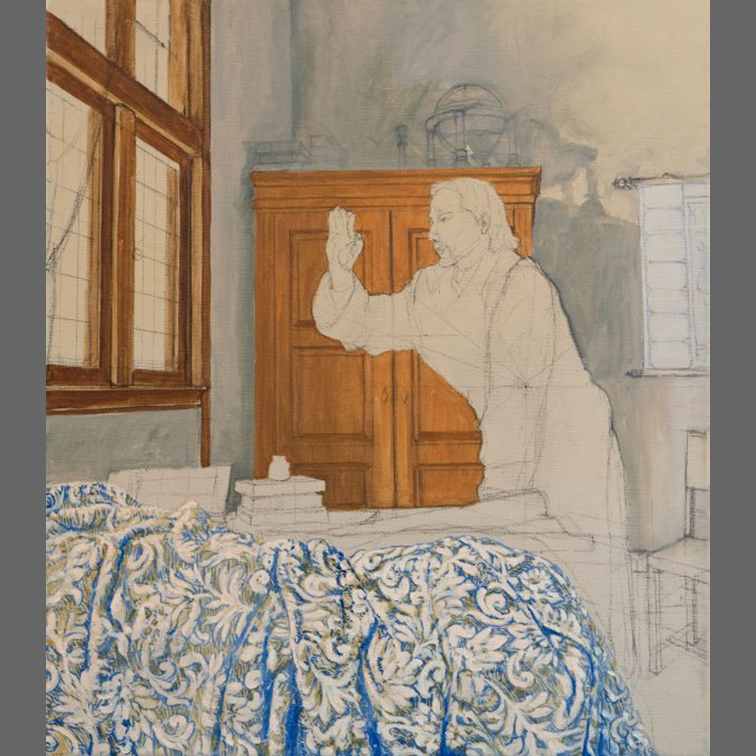

It all begins with “a point”. The initial layers are painted over a sketched outline that lays down every detail and focuses particularly on the vanishing point and the accurate perspective lines it is used to create.

The golden age

The arts benefited on an unprecedented scale from the economic prosperity enjoyed by the young Dutch Republic. In the middle of the 17th century, thousands and thousands of pieces were said to have been produced every year. Although only around ten percent of these have survived, old Dutch paintings can be found in countless galleries around the world.

1. Tangible success

The Golden Age brought great wealth to traders, merchants, artisans and farmers. They wanted to see their status reflected in their country’s artwork. This resulted in artists’ focus shifting to the everyday lives of their subjects, especially the middle class.

2. Remarkable realism

Rembrandt, Vermeer and van der Spelt measured their abilities according to how true to life they could make their paintings. This notion dates back to antiquity and mirrors the famous contest between Parrhasius and Zeuxis, when the former was heralded the better artist thanks to his painting of a deceptively realistic curtain. Rembrandt repeats this deception in his piece entitled The Holy Family with a Curtain.

3. Creation of space

The use of perspective is a legacy of the Renaissance. The painters used the technique of pronounced shortening to increase the illusion of depth and extend the pictorial space. This method is not only used when painting landscapes, but is also applied to studios, studies, lounges, courtyards and banquet halls.

4. Patriotism

In 1648, the Netherlands finally won their hard-earned independence from the Spanish crown. The feelings of patriotism among the country’s artists are reflected in their fondness of painting landscapes depicting the characteristic elements of the Dutch countryside.

5. Niches

Less notable Dutch artists sought out their fortune by developing areas of specialism. Besides painting the typical landscapes or portraits, some set about concentrating on unusual niches, such as still lifes of fish.

Eras of art in the KAIROS project

Medieval art

Early Netherlandish painting

Italian Renaissance

Mannerism

Early Baroque

Rokoko